April 2023 | Download PDF

Our first in this series goes back to basics as we look at what the word money really means.

These two questions don’t garner the attention they deserve; considering that money generally forms half of every transaction made throughout the global economy. The late economist Bernard Lietaer once said:

A common misconception is that most of the money we use is created by the government and/or the central bank. But as the Bank of England itself admits, the notes and coins that comprise public money only make up 3% of the money supply.

Most of the rest – around 80%, according to the BoE – comes into existence when banks issue loans. And those loans don’t come from a pre-existing pool of savings. Instead, as the BoE effectively admitted in 2014, banks create loans out of thin air, and simultaneously, the related deposit.

In other words, most money is interest-bearing debt. This has huge implications for how the economy functions, which we’ll discuss in a later instalment of this series.

To answer that question, a good place to start is to consider the functions it serves. Money has three main functions: as a store of value, a unit of account and most importantly a medium of exchange. This third function is the quintessential purpose of money. Lietaer defined money as “an agreement within a community to use something standardised as a medium of exchange”.

It bears noting that most currencies, that have become broadly accepted, did not have all three of the aforementioned features at the onset of their use.

Besides its three basic functions, money has a number of fundamental properties. It must be portable, divisible and durable. And historically it has been scarce.

Gold, for example, is exceptionally rare in the earth’s crust, and is difficult and costly to recover. Gold also does not corrode or ruin, and we have accumulated a vast quantity of gold above ground over thousands of years. As such, its growth rate is very low (around 1.5% per annum). Throughout history, money has come in all shapes and sizes, from grains of salt (which gave rise to the word ‘salary’) to ingots of silver.Over the course of history people have used shells, cattle, precious stones and, in times of turmoil, even cigarettes and alcohol as currency.

Today’s monetary system is different from many of its predecessors in one key aspect: it is not backed by a precious metal, commodity or any other scarce resource. It is simply money by government decree or fiat (Latin for “let it be done”) – hence the term ‘fiat currency’. As a consequence, there are now virtually no constraints on how much money can be created.

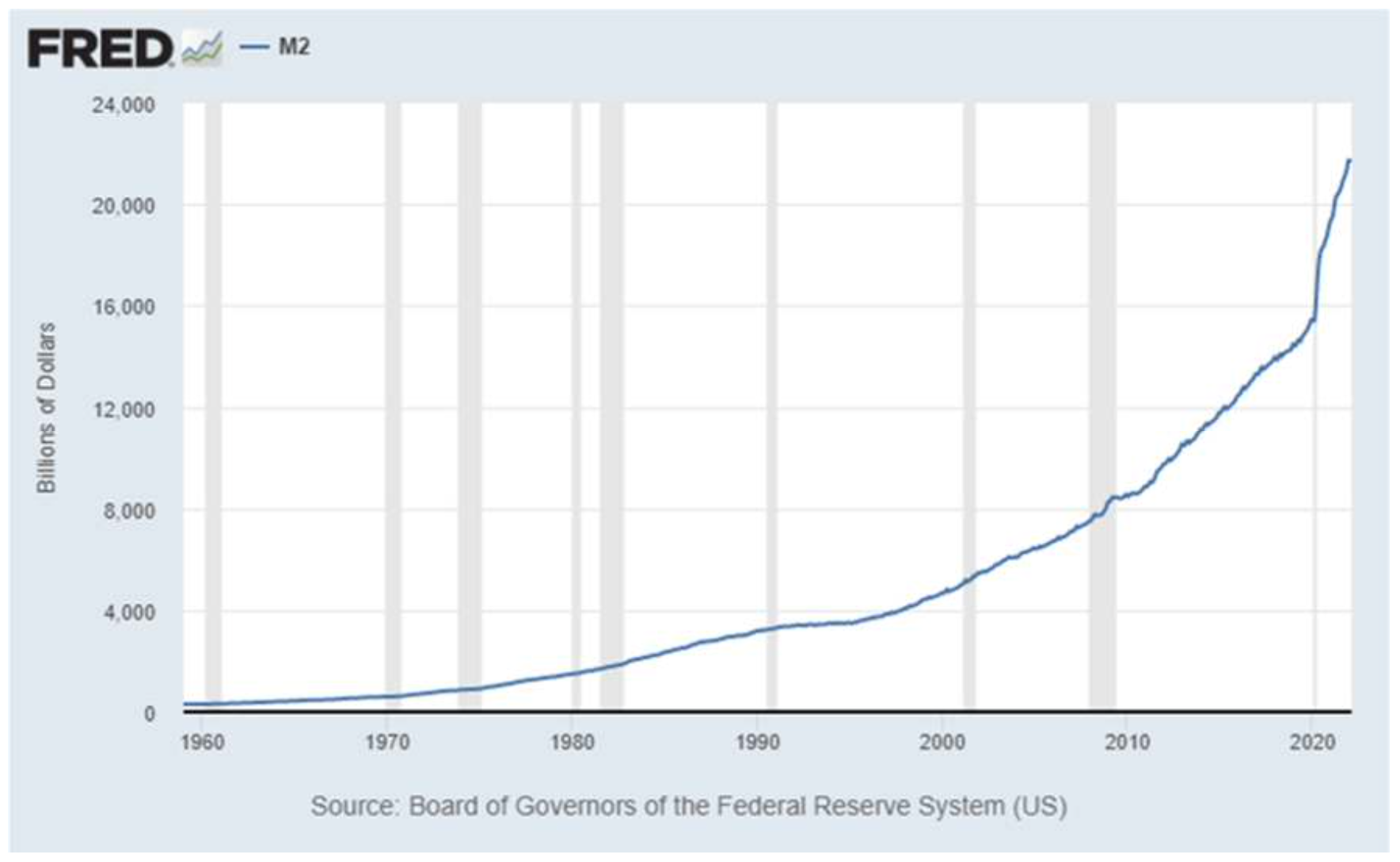

The result can be seen in the graph below. Over the past 63 years, the US Broad Money supply, or M2, has increased more than 70-fold from around $300 billion in 1960 to over $21,000 billion today. This trend, as the graph shows, is accelerating.

It is the same story for most fiat currencies, including the British pound. The result has been a previously gradual but now rapidly accelerating erosion of purchasing power. All but the wealthiest people and businesses are feeling its effects. For decades, the impact on broad price inflation was more or less moderate. But even low price inflation, compounded over decades, takes a significant toll.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and central banks stepped on the gas. They unleashed unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus at a time of sharply reduced economic activity, supply chain shocks and bottlenecks. By the end of 2020 the money supply in the US was growing at an annual rate of 29%. The highest year‐end rate since 1943, when the world was at war.

The inevitable result has been double-digit inflation. Inflation then exacerbated by the supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the West’s backfiring sanctions on Russia.

Central banks were too slow to rein in the forces they had unleashed. They kept interest rates too low for too long. Over the last year they’ve been trying to undo the damage. By hiking rates at the fastest pace in decades they’ve only piled yet more stress on an already buckling financial system.

Of course, currencies have come and gone throughout history, some slowly, some more quickly. The Romans debased their coins over centuries; the French destroyed the Assignat in just seven years (1789-1796).

As financial and economic conditions worsen today, this series of articles intends to shed light on the nature of money.

By understanding money better, perhaps we can better navigate these turbulent times.

If you would like to discuss any of these matters further, please get in touch with your usual contact at Cartwright.

To discuss your specific requirements with a member of our team, please start by sending us a brief message or, if your enquiry is more urgent, call our Head Office on 01252 894 883 and we will be put you in contact with the right person.